Ye olde grammar myth

Back in 1864, Henry Alford, aka the Dean of Canterbury, published a usage manual called The Queen’s English. In it, he offhandedly raised the issue of split infinitives – and, in doing so, created a monster that still terrorises grammarians today. We’ll return to Alford in a moment. But first . . .

What is an infinitive?

An infinitive is the most basic form of a verb. The infinitive usually takes the form to + verb, e.g. to go. This is called the full infinitive. When the to is dropped, e.g. go, it is called the bare infinitive.

The infinitive is the starting point from which a verb can be conjugated – that is, changed to reflect subject, mood or tense. For example, from the full infinitive to go we get goes, went, gone and going, depending on the context. But the full infinitive often appears in sentences as it is, unconjugated:

Are you ready to go?

To go there has always been a dream of mine.

He’s going to go with me.

What is a split infinitive?

When something – usually an adverb – comes in the middle of an infinitive, in between to and the verb, we say the infinitive has been split.

Are you ready to actually go?

To finally go there has always been a dream of mine.

He’s going to happily go with me.

And, of course, the most famous example of all:

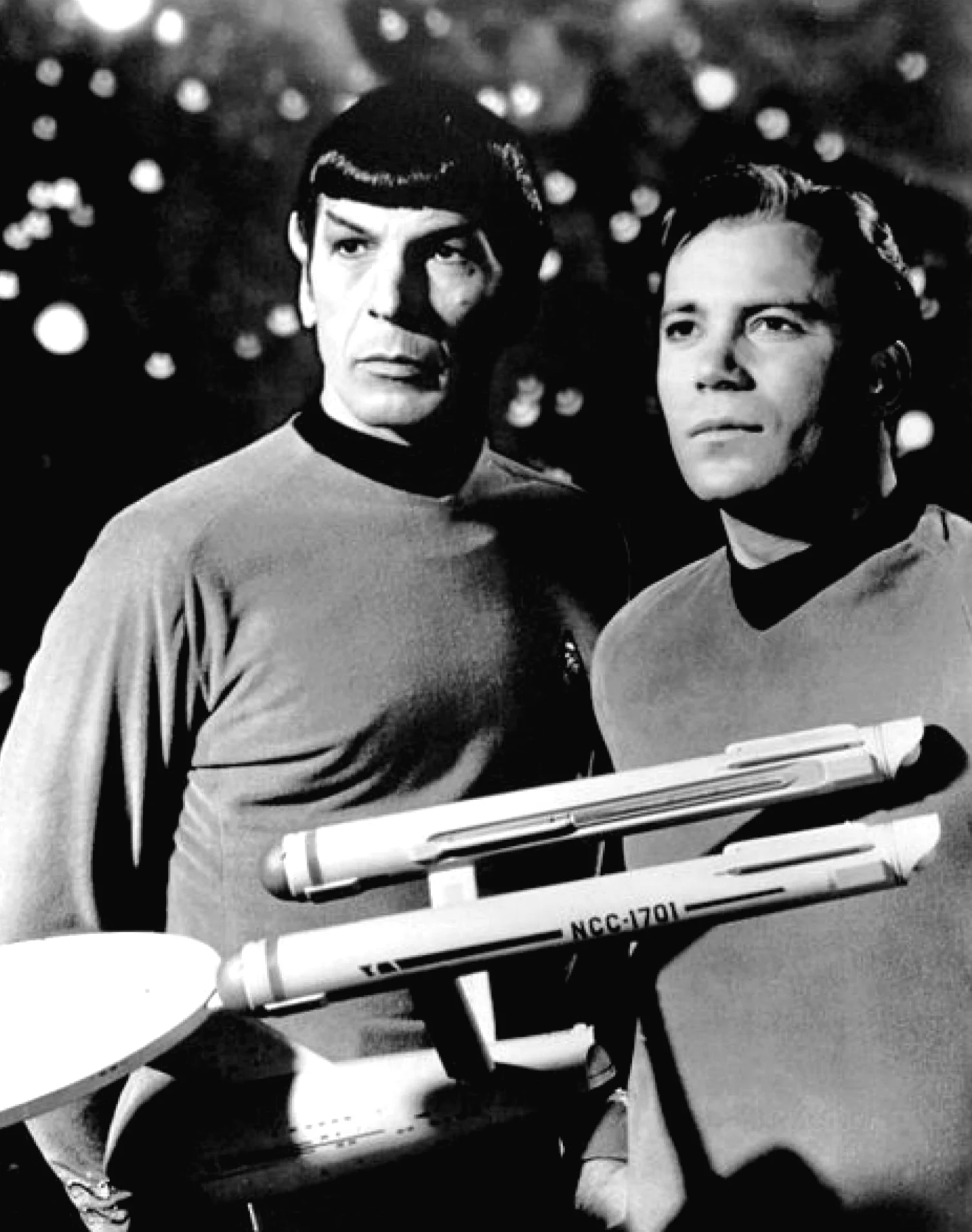

To boldly go where no man has gone before.

The Alford effect

Here’s what Henry Alford said about split infinitives:

A correspondent states as his own usage, and defends, the insertion of an adverb between the sign of the infinitive mood and the verb. He gives as an instance, “to scientifically illustrate.” But surely this is a practice entirely unknown to English speakers and writers. It seems to me, that we ever regard the to of the infinitive as inseparable from its verb. And when we have already a choice between two forms of expression, “scientifically to illustrate,” and “to illustrate scientifically,” there seems no good reason for flying in the face of common usage.

In other words, “Some guy wrote to me and said he likes to split infinitives. But I’ve never seen anyone else do that, and it’s easy to avoid, so I think he’s probably wrong.”

Hardly confidence-inspiring, especially when you find out that writers of the time actually were splitting infinitives, with gay abandon, right under Alford’s nose. But we can’t really blame him for the fact that his wishy-washy observation somehow morphed into a “rule” that was taught to screeds of schoolchildren. Even today, plenty of people insist that splitting infinitives is verboten, even though not a single respectable style manual agrees.

Usually, I follow even these controversial rules where possible, just to keep pedantic readers happy (see my posts on different than/to/from, that vs which, regime vs regimen, on to vs onto, begs the question and comprise). But this is where I draw the line. We can’t let a 207-year-old churchman tell us how to write, especially when every authority since him has disagreed. So, my friends, you have my permission to unabashedly split infinitives wherever your heart desires.